Tutorial: Intro to React

This tutorial doesn’t assume any existing React knowledge.

Before We Start the Tutorial

We will build a small game during this tutorial. You might be tempted to skip it because you’re not building games — but give it a chance. The techniques you’ll learn in the tutorial are fundamental to building any React app, and mastering it will give you a deep understanding of React.

Tip

This tutorial is designed for people who prefer to learn by doing. If you prefer learning concepts from the ground up, check out our step-by-step guide. You might find this tutorial and the guide complementary to each other.

The tutorial is divided into several sections:

- Setup for the Tutorial will give you a starting point to follow the tutorial.

- Overview will teach you the fundamentals of React: components, props, and state.

- Completing the Game will teach you the most common techniques in React development.

- Adding Time Travel will give you a deeper insight into the unique strengths of React.

You don’t have to complete all of the sections at once to get the value out of this tutorial. Try to get as far as you can — even if it’s one or two sections.

What Are We Building?

In this tutorial, we’ll show how to build an interactive tic-tac-toe game with React.

You can see what we’ll be building here: Final Result. If the code doesn’t make sense to you, or if you are unfamiliar with the code’s syntax, don’t worry! The goal of this tutorial is to help you understand React and its syntax.

We recommend that you check out the tic-tac-toe game before continuing with the tutorial. One of the features that you’ll notice is that there is a numbered list to the right of the game’s board. This list gives you a history of all of the moves that have occurred in the game, and it is updated as the game progresses.

You can close the tic-tac-toe game once you’re familiar with it. We’ll be starting from a simpler template in this tutorial. Our next step is to set you up so that you can start building the game.

Prerequisites

We’ll assume that you have some familiarity with HTML and JavaScript, but you should be able to follow along even if you’re coming from a different programming language. We’ll also assume that you’re familiar with programming concepts like functions, objects, arrays, and to a lesser extent, classes.

If you need to review JavaScript, we recommend reading this guide. Note that we’re also using some features from ES6 — a recent version of JavaScript. In this tutorial, we’re using arrow functions, classes, let, and const statements. You can use the Babel REPL to check what ES6 code compiles to.

Setup for the Tutorial

There are two ways to complete this tutorial: you can either write the code in your browser, or you can set up a local development environment on your computer.

Setup Option 1: Write Code in the Browser

This is the quickest way to get started!

First, open this Starter Code in a new tab. The new tab should display an empty tic-tac-toe game board and React code. We will be editing the React code in this tutorial.

You can now skip the second setup option, and go to the Overview section to get an overview of React.

Setup Option 2: Local Development Environment

This is completely optional and not required for this tutorial!

Optional: Instructions for following along locally using your preferred text editor

This setup requires more work but allows you to complete the tutorial using an editor of your choice. Here are the steps to follow:

- Make sure you have a recent version of Node.js installed.

- Follow the installation instructions for Create React App to make a new project.

npx create-react-app my-app- Delete all files in the

src/folder of the new project

Note:

Don’t delete the entire

srcfolder, just the original source files inside it. We’ll replace the default source files with examples for this project in the next step.

cd my-app

cd src

# If you're using a Mac or Linux:

rm -f *

# Or, if you're on Windows:

del *

# Then, switch back to the project folder

cd ..- Add a file named

index.cssin thesrc/folder with this CSS code. - Add a file named

index.jsin thesrc/folder with this JS code. - Add these three lines to the top of

index.jsin thesrc/folder:

import React from 'react';

import ReactDOM from 'react-dom';

import './index.css';Now if you run npm start in the project folder and open http://localhost:3000 in the browser, you should see an empty tic-tac-toe field.

We recommend following these instructions to configure syntax highlighting for your editor.

Help, I’m Stuck!

If you get stuck, check out the community support resources. In particular, Reactiflux Chat is a great way to get help quickly. If you don’t receive an answer, or if you remain stuck, please file an issue, and we’ll help you out.

Overview

Now that you’re set up, let’s get an overview of React!

What Is React?

React is a declarative, efficient, and flexible JavaScript library for building user interfaces. It lets you compose complex UIs from small and isolated pieces of code called “components”.

React has a few different kinds of components, but we’ll start with React.Component subclasses:

class ShoppingList extends React.Component {

render() {

return (

<div className="shopping-list">

<h1>Shopping List for {this.props.name}</h1>

<ul>

<li>Instagram</li>

<li>WhatsApp</li>

<li>Oculus</li>

</ul>

</div>

);

}

}

// Example usage: <ShoppingList name="Mark" />We’ll get to the funny XML-like tags soon. We use components to tell React what we want to see on the screen. When our data changes, React will efficiently update and re-render our components.

Here, ShoppingList is a React component class, or React component type. A component takes in parameters, called props (short for “properties”), and returns a hierarchy of views to display via the render method.

The render method returns a description of what you want to see on the screen. React takes the description and displays the result. In particular, render returns a React element, which is a lightweight description of what to render. Most React developers use a special syntax called “JSX” which makes these structures easier to write. The <div /> syntax is transformed at build time to React.createElement('div'). The example above is equivalent to:

return React.createElement('div', {className: 'shopping-list'},

React.createElement('h1', /* ... h1 children ... */),

React.createElement('ul', /* ... ul children ... */)

);If you’re curious, createElement() is described in more detail in the API reference, but we won’t be using it in this tutorial. Instead, we will keep using JSX.

JSX comes with the full power of JavaScript. You can put any JavaScript expressions within braces inside JSX. Each React element is a JavaScript object that you can store in a variable or pass around in your program.

The ShoppingList component above only renders built-in DOM components like <div /> and <li />. But you can compose and render custom React components too. For example, we can now refer to the whole shopping list by writing <ShoppingList />. Each React component is encapsulated and can operate independently; this allows you to build complex UIs from simple components.

Inspecting the Starter Code

If you’re going to work on the tutorial in your browser, open this code in a new tab: Starter Code. If you’re going to work on the tutorial locally, instead open src/index.js in your project folder (you have already touched this file during the setup).

This Starter Code is the base of what we’re building. We’ve provided the CSS styling so that you only need to focus on learning React and programming the tic-tac-toe game.

By inspecting the code, you’ll notice that we have three React components:

- Square

- Board

- Game

The Square component renders a single <button> and the Board renders 9 squares. The Game component renders a board with placeholder values which we’ll modify later. There are currently no interactive components.

Passing Data Through Props

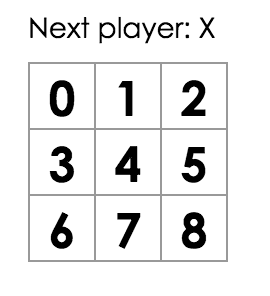

To get our feet wet, let’s try passing some data from our Board component to our Square component.

We strongly recommend typing code by hand as you’re working through the tutorial and not using copy/paste. This will help you develop muscle memory and a stronger understanding.

In Board’s renderSquare method, change the code to pass a prop called value to the Square:

class Board extends React.Component {

renderSquare(i) {

return <Square value={i} />; }

}Change Square’s render method to show that value by replacing {/* TODO */} with {this.props.value}:

class Square extends React.Component {

render() {

return (

<button className="square">

{this.props.value} </button>

);

}

}Before:

After: You should see a number in each square in the rendered output.

View the full code at this point

Congratulations! You’ve just “passed a prop” from a parent Board component to a child Square component. Passing props is how information flows in React apps, from parents to children.

Making an Interactive Component

Let’s fill the Square component with an “X” when we click it.

First, change the button tag that is returned from the Square component’s render() function to this:

class Square extends React.Component {

render() {

return (

<button className="square" onClick={function() { console.log('click'); }}> {this.props.value}

</button>

);

}

}If you click on a Square now, you should see ‘click’ in your browser’s devtools console.

Note

To save typing and avoid the confusing behavior of

this, we will use the arrow function syntax for event handlers here and further below:class Square extends React.Component { render() { return ( <button className="square" onClick={() => console.log('click')}> {this.props.value} </button> ); } }Notice how with

onClick={() => console.log('click')}, we’re passing a function as theonClickprop. React will only call this function after a click. Forgetting() =>and writingonClick={console.log('click')}is a common mistake, and would fire every time the component re-renders.

As a next step, we want the Square component to “remember” that it got clicked, and fill it with an “X” mark. To “remember” things, components use state.

React components can have state by setting this.state in their constructors. this.state should be considered as private to a React component that it’s defined in. Let’s store the current value of the Square in this.state, and change it when the Square is clicked.

First, we’ll add a constructor to the class to initialize the state:

class Square extends React.Component {

constructor(props) { super(props); this.state = { value: null, }; }

render() {

return (

<button className="square" onClick={() => console.log('click')}>

{this.props.value}

</button>

);

}

}Note

In JavaScript classes, you need to always call

superwhen defining the constructor of a subclass. All React component classes that have aconstructorshould start with asuper(props)call.

Now we’ll change the Square’s render method to display the current state’s value when clicked:

- Replace

this.props.valuewiththis.state.valueinside the<button>tag. - Replace the

onClick={...}event handler withonClick={() => this.setState({value: 'X'})}. - Put the

classNameandonClickprops on separate lines for better readability.

After these changes, the <button> tag that is returned by the Square’s render method looks like this:

class Square extends React.Component {

constructor(props) {

super(props);

this.state = {

value: null,

};

}

render() {

return (

<button

className="square" onClick={() => this.setState({value: 'X'})} >

{this.state.value} </button>

);

}

}By calling this.setState from an onClick handler in the Square’s render method, we tell React to re-render that Square whenever its <button> is clicked. After the update, the Square’s this.state.value will be 'X', so we’ll see the X on the game board. If you click on any Square, an X should show up.

When you call setState in a component, React automatically updates the child components inside of it too.

View the full code at this point

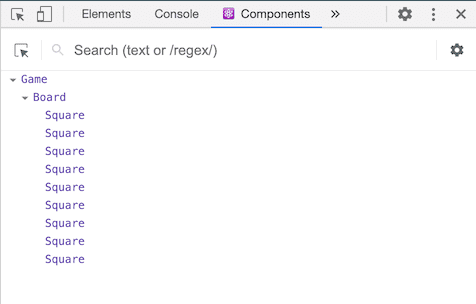

Developer Tools

The React Devtools extension for Chrome and Firefox lets you inspect a React component tree with your browser’s developer tools.

The React DevTools let you check the props and the state of your React components.

After installing React DevTools, you can right-click on any element on the page, click “Inspect” to open the developer tools, and the React tabs (“⚛️ Components” and “⚛️ Profiler”) will appear as the last tabs to the right. Use “⚛️ Components” to inspect the component tree.

However, note there are a few extra steps to get it working with CodePen:

- Log in or register and confirm your email (required to prevent spam).

- Click the “Fork” button.

- Click “Change View” and then choose “Debug mode”.

- In the new tab that opens, the devtools should now have a React tab.

Completing the Game

We now have the basic building blocks for our tic-tac-toe game. To have a complete game, we now need to alternate placing “X”s and “O”s on the board, and we need a way to determine a winner.

Lifting State Up

Currently, each Square component maintains the game’s state. To check for a winner, we’ll maintain the value of each of the 9 squares in one location.

We may think that Board should just ask each Square for the Square’s state. Although this approach is possible in React, we discourage it because the code becomes difficult to understand, susceptible to bugs, and hard to refactor. Instead, the best approach is to store the game’s state in the parent Board component instead of in each Square. The Board component can tell each Square what to display by passing a prop, just like we did when we passed a number to each Square.

To collect data from multiple children, or to have two child components communicate with each other, you need to declare the shared state in their parent component instead. The parent component can pass the state back down to the children by using props; this keeps the child components in sync with each other and with the parent component.

Lifting state into a parent component is common when React components are refactored — let’s take this opportunity to try it out.

Add a constructor to the Board and set the Board’s initial state to contain an array of 9 nulls corresponding to the 9 squares:

class Board extends React.Component {

constructor(props) { super(props); this.state = { squares: Array(9).fill(null), }; }

renderSquare(i) {

return <Square value={i} />;

}When we fill the board in later, the this.state.squares array will look something like this:

[

'O', null, 'X',

'X', 'X', 'O',

'O', null, null,

]The Board’s renderSquare method currently looks like this:

renderSquare(i) {

return <Square value={i} />;

}In the beginning, we passed the value prop down from the Board to show numbers from 0 to 8 in every Square. In a different previous step, we replaced the numbers with an “X” mark determined by Square’s own state. This is why Square currently ignores the value prop passed to it by the Board.

We will now use the prop passing mechanism again. We will modify the Board to instruct each individual Square about its current value ('X', 'O', or null). We have already defined the squares array in the Board’s constructor, and we will modify the Board’s renderSquare method to read from it:

renderSquare(i) {

return <Square value={this.state.squares[i]} />; }View the full code at this point

Each Square will now receive a value prop that will either be 'X', 'O', or null for empty squares.

Next, we need to change what happens when a Square is clicked. The Board component now maintains which squares are filled. We need to create a way for the Square to update the Board’s state. Since state is considered to be private to a component that defines it, we cannot update the Board’s state directly from Square.

Instead, we’ll pass down a function from the Board to the Square, and we’ll have Square call that function when a square is clicked. We’ll change the renderSquare method in Board to:

renderSquare(i) {

return (

<Square

value={this.state.squares[i]}

onClick={() => this.handleClick(i)} />

);

}Note

We split the returned element into multiple lines for readability, and added parentheses so that JavaScript doesn’t insert a semicolon after

returnand break our code.

Now we’re passing down two props from Board to Square: value and onClick. The onClick prop is a function that Square can call when clicked. We’ll make the following changes to Square:

- Replace

this.state.valuewiththis.props.valuein Square’srendermethod - Replace

this.setState()withthis.props.onClick()in Square’srendermethod - Delete the

constructorfrom Square because Square no longer keeps track of the game’s state

After these changes, the Square component looks like this:

class Square extends React.Component { render() { return (

<button

className="square"

onClick={() => this.props.onClick()} >

{this.props.value} </button>

);

}

}When a Square is clicked, the onClick function provided by the Board is called. Here’s a review of how this is achieved:

- The

onClickprop on the built-in DOM<button>component tells React to set up a click event listener. - When the button is clicked, React will call the

onClickevent handler that is defined in Square’srender()method. - This event handler calls

this.props.onClick(). The Square’sonClickprop was specified by the Board. - Since the Board passed

onClick={() => this.handleClick(i)}to Square, the Square calls the Board’shandleClick(i)when clicked. - We have not defined the

handleClick()method yet, so our code crashes. If you click a square now, you should see a red error screen saying something like “this.handleClick is not a function”.

Note

The DOM

<button>element’sonClickattribute has a special meaning to React because it is a built-in component. For custom components like Square, the naming is up to you. We could give any name to the Square’sonClickprop or Board’shandleClickmethod, and the code would work the same. In React, it’s conventional to useon[Event]names for props which represent events andhandle[Event]for the methods which handle the events.

When we try to click a Square, we should get an error because we haven’t defined handleClick yet. We’ll now add handleClick to the Board class:

class Board extends React.Component {

constructor(props) {

super(props);

this.state = {

squares: Array(9).fill(null),

};

}

handleClick(i) { const squares = this.state.squares.slice(); squares[i] = 'X'; this.setState({squares: squares}); }

renderSquare(i) {

return (

<Square

value={this.state.squares[i]}

onClick={() => this.handleClick(i)}

/>

);

}

render() {

const status = 'Next player: X';

return (

<div>

<div className="status">{status}</div>

<div className="board-row">

{this.renderSquare(0)}

{this.renderSquare(1)}

{this.renderSquare(2)}

</div>

<div className="board-row">

{this.renderSquare(3)}

{this.renderSquare(4)}

{this.renderSquare(5)}

</div>

<div className="board-row">

{this.renderSquare(6)}

{this.renderSquare(7)}

{this.renderSquare(8)}

</div>

</div>

);

}

}View the full code at this point

After these changes, we’re again able to click on the Squares to fill them, the same as we had before. However, now the state is stored in the Board component instead of the individual Square components. When the Board’s state changes, the Square components re-render automatically. Keeping the state of all squares in the Board component will allow it to determine the winner in the future.

Since the Square components no longer maintain state, the Square components receive values from the Board component and inform the Board component when they’re clicked. In React terms, the Square components are now controlled components. The Board has full control over them.

Note how in handleClick, we call .slice() to create a copy of the squares array to modify instead of modifying the existing array. We will explain why we create a copy of the squares array in the next section.

Why Immutability Is Important

In the previous code example, we suggested that you create a copy of the squares array using the slice() method instead of modifying the existing array. We’ll now discuss immutability and why immutability is important to learn.

There are generally two approaches to changing data. The first approach is to mutate the data by directly changing the data’s values. The second approach is to replace the data with a new copy which has the desired changes.

Data Change with Mutation

var player = {score: 1, name: 'Jeff'};

player.score = 2;

// Now player is {score: 2, name: 'Jeff'}Data Change without Mutation

var player = {score: 1, name: 'Jeff'};

var newPlayer = Object.assign({}, player, {score: 2});

// Now player is unchanged, but newPlayer is {score: 2, name: 'Jeff'}

// Or if you are using object spread syntax proposal, you can write:

// var newPlayer = {...player, score: 2};The end result is the same but by not mutating (or changing the underlying data) directly, we gain several benefits described below.

Complex Features Become Simple

Immutability makes complex features much easier to implement. Later in this tutorial, we will implement a “time travel” feature that allows us to review the tic-tac-toe game’s history and “jump back” to previous moves. This functionality isn’t specific to games — an ability to undo and redo certain actions is a common requirement in applications. Avoiding direct data mutation lets us keep previous versions of the game’s history intact, and reuse them later.

Detecting Changes

Detecting changes in mutable objects is difficult because they are modified directly. This detection requires the mutable object to be compared to previous copies of itself and the entire object tree to be traversed.

Detecting changes in immutable objects is considerably easier. If the immutable object that is being referenced is different than the previous one, then the object has changed.

Determining When to Re-Render in React

The main benefit of immutability is that it helps you build pure components in React. Immutable data can easily determine if changes have been made, which helps to determine when a component requires re-rendering.

You can learn more about shouldComponentUpdate() and how you can build pure components by reading Optimizing Performance.

Function Components

We’ll now change the Square to be a function component.

In React, function components are a simpler way to write components that only contain a render method and don’t have their own state. Instead of defining a class which extends React.Component, we can write a function that takes props as input and returns what should be rendered. Function components are less tedious to write than classes, and many components can be expressed this way.

Replace the Square class with this function:

function Square(props) {

return (

<button className="square" onClick={props.onClick}>

{props.value}

</button>

);

}We have changed this.props to props both times it appears.

View the full code at this point

Note

When we modified the Square to be a function component, we also changed

onClick={() => this.props.onClick()}to a shorteronClick={props.onClick}(note the lack of parentheses on both sides).

Taking Turns

We now need to fix an obvious defect in our tic-tac-toe game: the “O”s cannot be marked on the board.

We’ll set the first move to be “X” by default. We can set this default by modifying the initial state in our Board constructor:

class Board extends React.Component {

constructor(props) {

super(props);

this.state = {

squares: Array(9).fill(null),

xIsNext: true, };

}Each time a player moves, xIsNext (a boolean) will be flipped to determine which player goes next and the game’s state will be saved. We’ll update the Board’s handleClick function to flip the value of xIsNext:

handleClick(i) {

const squares = this.state.squares.slice();

squares[i] = this.state.xIsNext ? 'X' : 'O'; this.setState({

squares: squares,

xIsNext: !this.state.xIsNext, });

}With this change, “X”s and “O”s can take turns. Try it!

Let’s also change the “status” text in Board’s render so that it displays which player has the next turn:

render() {

const status = 'Next player: ' + (this.state.xIsNext ? 'X' : 'O');

return (

// the rest has not changedAfter applying these changes, you should have this Board component:

class Board extends React.Component {

constructor(props) {

super(props);

this.state = {

squares: Array(9).fill(null),

xIsNext: true, };

}

handleClick(i) {

const squares = this.state.squares.slice(); squares[i] = this.state.xIsNext ? 'X' : 'O'; this.setState({ squares: squares, xIsNext: !this.state.xIsNext, }); }

renderSquare(i) {

return (

<Square

value={this.state.squares[i]}

onClick={() => this.handleClick(i)}

/>

);

}

render() {

const status = 'Next player: ' + (this.state.xIsNext ? 'X' : 'O');

return (

<div>

<div className="status">{status}</div>

<div className="board-row">

{this.renderSquare(0)}

{this.renderSquare(1)}

{this.renderSquare(2)}

</div>

<div className="board-row">

{this.renderSquare(3)}

{this.renderSquare(4)}

{this.renderSquare(5)}

</div>

<div className="board-row">

{this.renderSquare(6)}

{this.renderSquare(7)}

{this.renderSquare(8)}

</div>

</div>

);

}

}View the full code at this point

Declaring a Winner

Now that we show which player’s turn is next, we should also show when the game is won and there are no more turns to make. Copy this helper function and paste it at the end of the file:

function calculateWinner(squares) {

const lines = [

[0, 1, 2],

[3, 4, 5],

[6, 7, 8],

[0, 3, 6],

[1, 4, 7],

[2, 5, 8],

[0, 4, 8],

[2, 4, 6],

];

for (let i = 0; i < lines.length; i++) {

const [a, b, c] = lines[i];

if (squares[a] && squares[a] === squares[b] && squares[a] === squares[c]) {

return squares[a];

}

}

return null;

}Given an array of 9 squares, this function will check for a winner and return 'X', 'O', or null as appropriate.

We will call calculateWinner(squares) in the Board’s render function to check if a player has won. If a player has won, we can display text such as “Winner: X” or “Winner: O”. We’ll replace the status declaration in Board’s render function with this code:

render() {

const winner = calculateWinner(this.state.squares); let status; if (winner) { status = 'Winner: ' + winner; } else { status = 'Next player: ' + (this.state.xIsNext ? 'X' : 'O'); }

return (

// the rest has not changedWe can now change the Board’s handleClick function to return early by ignoring a click if someone has won the game or if a Square is already filled:

handleClick(i) {

const squares = this.state.squares.slice();

if (calculateWinner(squares) || squares[i]) { return; } squares[i] = this.state.xIsNext ? 'X' : 'O';

this.setState({

squares: squares,

xIsNext: !this.state.xIsNext,

});

}View the full code at this point

Congratulations! You now have a working tic-tac-toe game. And you’ve just learned the basics of React too. So you’re probably the real winner here.

Adding Time Travel

As a final exercise, let’s make it possible to “go back in time” to the previous moves in the game.

Storing a History of Moves

If we mutated the squares array, implementing time travel would be very difficult.

However, we used slice() to create a new copy of the squares array after every move, and treated it as immutable. This will allow us to store every past version of the squares array, and navigate between the turns that have already happened.

We’ll store the past squares arrays in another array called history. The history array represents all board states, from the first to the last move, and has a shape like this:

history = [

// Before first move

{

squares: [

null, null, null,

null, null, null,

null, null, null,

]

},

// After first move

{

squares: [

null, null, null,

null, 'X', null,

null, null, null,

]

},

// After second move

{

squares: [

null, null, null,

null, 'X', null,

null, null, 'O',

]

},

// ...

]Now we need to decide which component should own the history state.

Lifting State Up, Again

We’ll want the top-level Game component to display a list of past moves. It will need access to the history to do that, so we will place the history state in the top-level Game component.

Placing the history state into the Game component lets us remove the squares state from its child Board component. Just like we “lifted state up” from the Square component into the Board component, we are now lifting it up from the Board into the top-level Game component. This gives the Game component full control over the Board’s data, and lets it instruct the Board to render previous turns from the history.

First, we’ll set up the initial state for the Game component within its constructor:

class Game extends React.Component {

constructor(props) { super(props); this.state = { history: [{ squares: Array(9).fill(null), }], xIsNext: true, }; }

render() {

return (

<div className="game">

<div className="game-board">

<Board />

</div>

<div className="game-info">

<div>{/* status */}</div>

<ol>{/* TODO */}</ol>

</div>

</div>

);

}

}Next, we’ll have the Board component receive squares and onClick props from the Game component. Since we now have a single click handler in Board for many Squares, we’ll need to pass the location of each Square into the onClick handler to indicate which Square was clicked. Here are the required steps to transform the Board component:

- Delete the

constructorin Board. - Replace

this.state.squares[i]withthis.props.squares[i]in Board’srenderSquare. - Replace

this.handleClick(i)withthis.props.onClick(i)in Board’srenderSquare.

The Board component now looks like this:

class Board extends React.Component {

handleClick(i) {

const squares = this.state.squares.slice();

if (calculateWinner(squares) || squares[i]) {

return;

}

squares[i] = this.state.xIsNext ? 'X' : 'O';

this.setState({

squares: squares,

xIsNext: !this.state.xIsNext,

});

}

renderSquare(i) {

return (

<Square

value={this.props.squares[i]} onClick={() => this.props.onClick(i)} />

);

}

render() {

const winner = calculateWinner(this.state.squares);

let status;

if (winner) {

status = 'Winner: ' + winner;

} else {

status = 'Next player: ' + (this.state.xIsNext ? 'X' : 'O');

}

return (

<div>

<div className="status">{status}</div>

<div className="board-row">

{this.renderSquare(0)}

{this.renderSquare(1)}

{this.renderSquare(2)}

</div>

<div className="board-row">

{this.renderSquare(3)}

{this.renderSquare(4)}

{this.renderSquare(5)}

</div>

<div className="board-row">

{this.renderSquare(6)}

{this.renderSquare(7)}

{this.renderSquare(8)}

</div>

</div>

);

}

}We’ll update the Game component’s render function to use the most recent history entry to determine and display the game’s status:

render() {

const history = this.state.history; const current = history[history.length - 1]; const winner = calculateWinner(current.squares); let status; if (winner) { status = 'Winner: ' + winner; } else { status = 'Next player: ' + (this.state.xIsNext ? 'X' : 'O'); }

return (

<div className="game">

<div className="game-board">

<Board squares={current.squares} onClick={(i) => this.handleClick(i)} /> </div>

<div className="game-info">

<div>{status}</div> <ol>{/* TODO */}</ol>

</div>

</div>

);

}Since the Game component is now rendering the game’s status, we can remove the corresponding code from the Board’s render method. After refactoring, the Board’s render function looks like this:

render() { return ( <div> <div className="board-row"> {this.renderSquare(0)}

{this.renderSquare(1)}

{this.renderSquare(2)}

</div>

<div className="board-row">

{this.renderSquare(3)}

{this.renderSquare(4)}

{this.renderSquare(5)}

</div>

<div className="board-row">

{this.renderSquare(6)}

{this.renderSquare(7)}

{this.renderSquare(8)}

</div>

</div>

);

}Finally, we need to move the handleClick method from the Board component to the Game component. We also need to modify handleClick because the Game component’s state is structured differently. Within the Game’s handleClick method, we concatenate new history entries onto history.

handleClick(i) {

const history = this.state.history; const current = history[history.length - 1]; const squares = current.squares.slice(); if (calculateWinner(squares) || squares[i]) {

return;

}

squares[i] = this.state.xIsNext ? 'X' : 'O';

this.setState({

history: history.concat([{ squares: squares, }]), xIsNext: !this.state.xIsNext,

});

}Note

Unlike the array

push()method you might be more familiar with, theconcat()method doesn’t mutate the original array, so we prefer it.

At this point, the Board component only needs the renderSquare and render methods. The game’s state and the handleClick method should be in the Game component.

View the full code at this point

Showing the Past Moves

Since we are recording the tic-tac-toe game’s history, we can now display it to the player as a list of past moves.

We learned earlier that React elements are first-class JavaScript objects; we can pass them around in our applications. To render multiple items in React, we can use an array of React elements.

In JavaScript, arrays have a map() method that is commonly used for mapping data to other data, for example:

const numbers = [1, 2, 3];

const doubled = numbers.map(x => x * 2); // [2, 4, 6]Using the map method, we can map our history of moves to React elements representing buttons on the screen, and display a list of buttons to “jump” to past moves.

Let’s map over the history in the Game’s render method:

render() {

const history = this.state.history;

const current = history[history.length - 1];

const winner = calculateWinner(current.squares);

const moves = history.map((step, move) => { const desc = move ? 'Go to move #' + move : 'Go to game start'; return ( <li> <button onClick={() => this.jumpTo(move)}>{desc}</button> </li> ); });

let status;

if (winner) {

status = 'Winner: ' + winner;

} else {

status = 'Next player: ' + (this.state.xIsNext ? 'X' : 'O');

}

return (

<div className="game">

<div className="game-board">

<Board

squares={current.squares}

onClick={(i) => this.handleClick(i)}

/>

</div>

<div className="game-info">

<div>{status}</div>

<ol>{moves}</ol> </div>

</div>

);

}View the full code at this point

As we iterate through history array, step variable refers to the current history element value, and move refers to the current history element index. We only interested in move here, hence step is not getting assigned to anything.

For each move in the tic-tac-toe game’s history, we create a list item <li> which contains a button <button>. The button has a onClick handler which calls a method called this.jumpTo(). We haven’t implemented the jumpTo() method yet. For now, we should see a list of the moves that have occurred in the game and a warning in the developer tools console that says:

Warning: Each child in an array or iterator should have a unique “key” prop. Check the render method of “Game”.

Let’s discuss what the above warning means.

Picking a Key

When we render a list, React stores some information about each rendered list item. When we update a list, React needs to determine what has changed. We could have added, removed, re-arranged, or updated the list’s items.

Imagine transitioning from

<li>Alexa: 7 tasks left</li>

<li>Ben: 5 tasks left</li>to

<li>Ben: 9 tasks left</li>

<li>Claudia: 8 tasks left</li>

<li>Alexa: 5 tasks left</li>In addition to the updated counts, a human reading this would probably say that we swapped Alexa and Ben’s ordering and inserted Claudia between Alexa and Ben. However, React is a computer program and does not know what we intended. Because React cannot know our intentions, we need to specify a key property for each list item to differentiate each list item from its siblings. One option would be to use the strings alexa, ben, claudia. If we were displaying data from a database, Alexa, Ben, and Claudia’s database IDs could be used as keys.

<li key={user.id}>{user.name}: {user.taskCount} tasks left</li>When a list is re-rendered, React takes each list item’s key and searches the previous list’s items for a matching key. If the current list has a key that didn’t exist before, React creates a component. If the current list is missing a key that existed in the previous list, React destroys the previous component. If two keys match, the corresponding component is moved. Keys tell React about the identity of each component which allows React to maintain state between re-renders. If a component’s key changes, the component will be destroyed and re-created with a new state.

key is a special and reserved property in React (along with ref, a more advanced feature). When an element is created, React extracts the key property and stores the key directly on the returned element. Even though key may look like it belongs in props, key cannot be referenced using this.props.key. React automatically uses key to decide which components to update. A component cannot inquire about its key.

It’s strongly recommended that you assign proper keys whenever you build dynamic lists. If you don’t have an appropriate key, you may want to consider restructuring your data so that you do.

If no key is specified, React will present a warning and use the array index as a key by default. Using the array index as a key is problematic when trying to re-order a list’s items or inserting/removing list items. Explicitly passing key={i} silences the warning but has the same problems as array indices and is not recommended in most cases.

Keys do not need to be globally unique; they only need to be unique between components and their siblings.

Implementing Time Travel

In the tic-tac-toe game’s history, each past move has a unique ID associated with it: it’s the sequential number of the move. The moves are never re-ordered, deleted, or inserted in the middle, so it’s safe to use the move index as a key.

In the Game component’s render method, we can add the key as <li key={move}> and React’s warning about keys should disappear:

const moves = history.map((step, move) => {

const desc = move ?

'Go to move #' + move :

'Go to game start';

return (

<li key={move}> <button onClick={() => this.jumpTo(move)}>{desc}</button>

</li>

);

});View the full code at this point

Clicking any of the list item’s buttons throws an error because the jumpTo method is undefined. Before we implement jumpTo, we’ll add stepNumber to the Game component’s state to indicate which step we’re currently viewing.

First, add stepNumber: 0 to the initial state in Game’s constructor:

class Game extends React.Component {

constructor(props) {

super(props);

this.state = {

history: [{

squares: Array(9).fill(null),

}],

stepNumber: 0, xIsNext: true,

};

}Next, we’ll define the jumpTo method in Game to update that stepNumber. We also set xIsNext to true if the number that we’re changing stepNumber to is even:

handleClick(i) {

// this method has not changed

}

jumpTo(step) { this.setState({ stepNumber: step, xIsNext: (step % 2) === 0, }); }

render() {

// this method has not changed

}Notice in jumpTo method, we haven’t updated history property of the state. That is because state updates are merged or in more simple words React will update only the properties mentioned in setState method leaving the remaining state as that is. For more info see the documentation.

We will now make a few changes to the Game’s handleClick method which fires when you click on a square.

The stepNumber state we’ve added reflects the move displayed to the user now. After we make a new move, we need to update stepNumber by adding stepNumber: history.length as part of the this.setState argument. This ensures we don’t get stuck showing the same move after a new one has been made.

We will also replace reading this.state.history with this.state.history.slice(0, this.state.stepNumber + 1). This ensures that if we “go back in time” and then make a new move from that point, we throw away all the “future” history that would now become incorrect.

handleClick(i) {

const history = this.state.history.slice(0, this.state.stepNumber + 1); const current = history[history.length - 1];

const squares = current.squares.slice();

if (calculateWinner(squares) || squares[i]) {

return;

}

squares[i] = this.state.xIsNext ? 'X' : 'O';

this.setState({

history: history.concat([{

squares: squares

}]),

stepNumber: history.length, xIsNext: !this.state.xIsNext,

});

}Finally, we will modify the Game component’s render method from always rendering the last move to rendering the currently selected move according to stepNumber:

render() {

const history = this.state.history;

const current = history[this.state.stepNumber]; const winner = calculateWinner(current.squares);

// the rest has not changedIf we click on any step in the game’s history, the tic-tac-toe board should immediately update to show what the board looked like after that step occurred.

View the full code at this point

Wrapping Up

Congratulations! You’ve created a tic-tac-toe game that:

- Lets you play tic-tac-toe,

- Indicates when a player has won the game,

- Stores a game’s history as a game progresses,

- Allows players to review a game’s history and see previous versions of a game’s board.

Nice work! We hope you now feel like you have a decent grasp of how React works.

Check out the final result here: Final Result.

If you have extra time or want to practice your new React skills, here are some ideas for improvements that you could make to the tic-tac-toe game which are listed in order of increasing difficulty:

- Display the location for each move in the format (col, row) in the move history list.

- Bold the currently selected item in the move list.

- Rewrite Board to use two loops to make the squares instead of hardcoding them.

- Add a toggle button that lets you sort the moves in either ascending or descending order.

- When someone wins, highlight the three squares that caused the win.

- When no one wins, display a message about the result being a draw.

Throughout this tutorial, we touched on React concepts including elements, components, props, and state. For a more detailed explanation of each of these topics, check out the rest of the documentation. To learn more about defining components, check out the React.Component API reference.